Most of Machen's fiction is short, and evokes wonder, terror, or both. His long short story "The Great God Pan" (1894), his first major success, caused a furore in London as the pagan demoness who is its central figure links horror with a prurient sexuality; a night spent with her leaves her victims grey, haunted and bound for death. Other stories around this time also explored paganism and sexuality. Most famous are "The Inmost Light" and "The White People". The latter is an eerie first-person account of a young girl's haunting by an evil statue she discovers in a wood, the fragility of her innocence creating a delicate balance between wonder and terror. Pagan horror is also central in The Three Impostors (1895) which is essentially a collection of short stories linked together in a single frame: the most often reprinted have been "The Black Seal", the story of an anthropologist who discovers a tribe of throwback hominids living in the Welsh mountains, and "The White Powder", which concerns an unfortunate young man's degeneration into primeval slime. All of these stories can be seen as examples of the fantastic genre, set identifiably in the real world, yet bound to disturb our sense of its familiar possibilities.

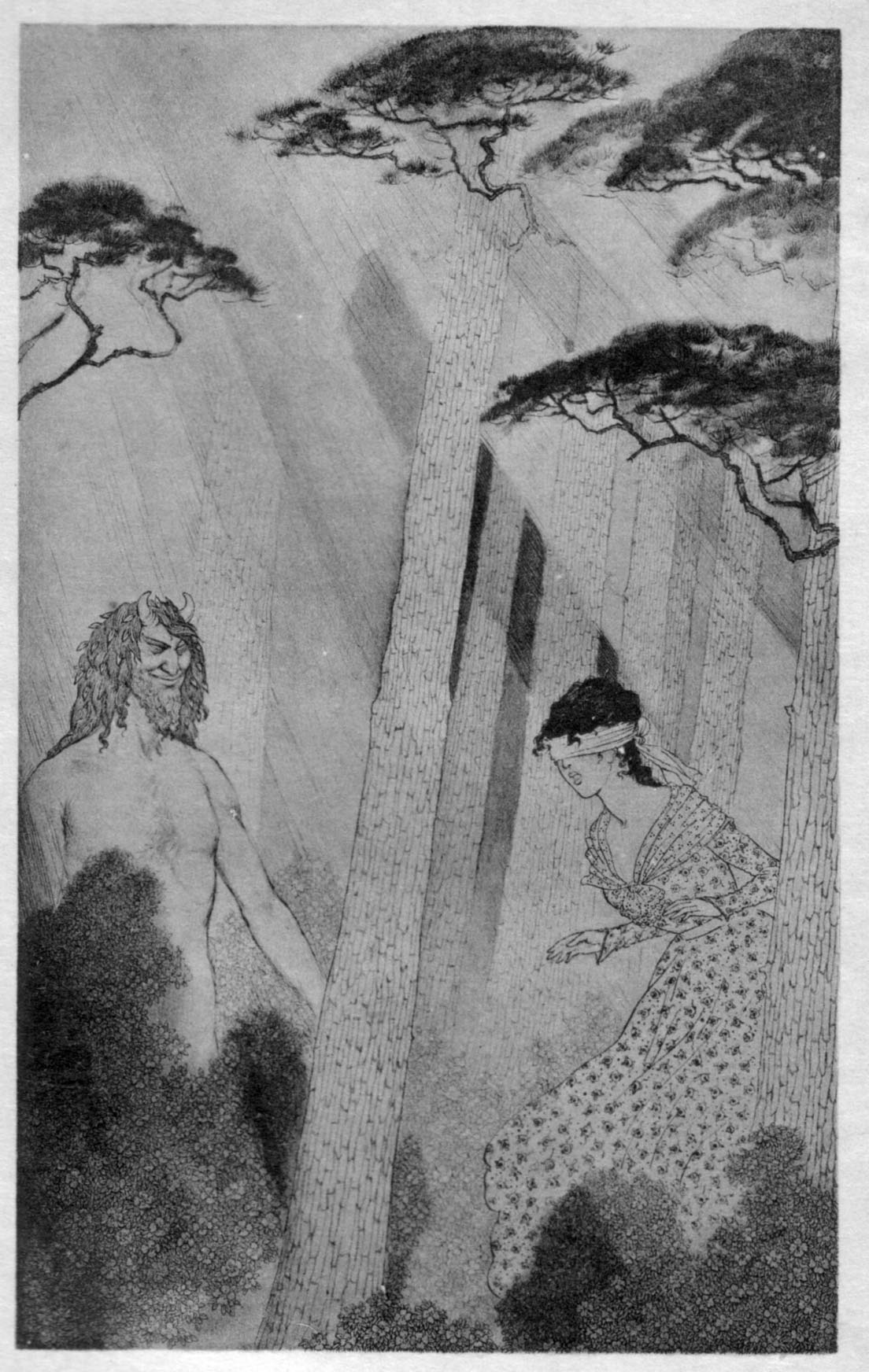

In all the above tales, malefic powers are evoked: something ancient and terrible - demon or primeval throwback - surfaces into the modern world. Like many tales of horror, these are moralistic; the reader is often encouraged to enjoy the rise of atavistic powers which punish those who have sinned. Machen had his first successes with this kind of work, which is still popular today; however, for many readers nowadays his finest fiction was written in the later 1890s. By this time his moralistic attitudes had become more liberal, and he was more prepared to explore paganism and 'damnation' from within, and even perhaps to allow that these same dark, pagan powers might have a regenerative possibility. Pre-eminent among these slightly later works is the novel The Hill of Dreams (1907), which charts the gradual possession of a young writer by a kind of pagan faun-creature who lives within him, rather as Stevenson's Hyde lives within Jekyll. This novel, often considered Machen's finest work, powerfully evokes both a dreamlike Roman past and a dark, hallucinatory modern London, irreconcilable alternate realities between which the young writer is destroyed. A series of very short pieces written at the same time, eventually collected under the title Ornaments in Jade, similarly shows a more ambiguously positive celebration of pagan sexual powers, and also demonstrates Machen's interest in the avant-garde prose poetry of the French decadence.

Around the end of the 1890s Machen began to be interested in the healing potential of a more orthodox mysticism. His novella "A Fragment of Life" chronicles the life of Edward Darnell, who begins the tale as a suburb-dwelling clerk but makes an inward and outward journey towards mysticism and the land of his birth, Wales. Of all Machen's works this is the most successful in imagining mystical rebirth in the context of the real world. A later novel The Secret Glory(1922) explores in similar vein the life of a schoolboy who embraces the grail-quest, to find ecstasy and martyrdom. The enigmatically titled "N", which Machen wrote when he was over seventy, is a kind of psychedelic fable which concerns the discovery of an alternate reality existing in the context of a humble, grey north London suburb. Machen's greatest power is thus, to bring together banal familiarity and impossible strangeness, to the enhancement of both.

Whether through the imagery of dark paganism or of mystical regeneration, Machen's fiction is consistent in its exploration of what he called ecstasy, a topic he explored fully in Hieroglyphics (1902) his work of literary theory. Though much of his non-fiction work is of polemical intent, and perhaps of lesser interest to readers today, his first volume of autobiography, Far Off Things (1922), has been widely celebrated for its mood of sustained reverie and its power to evoke a sense of wonder from landscape. Machen's temperament was intensely set against the materialism which he saw as the disease of his age; all of his works, both fiction and non-fiction, can be seen as polemic against the twin oppressions of business and science, and their secular visions of the world.